Photographer’s Website: https://sarafuller.com/

Last week I discussed the importance of forming a relationship with your professors. I have gotten close with a few of my professors throughout my student career at Pace University and I’m so thankful for all that they have helped me with. This week, one of my professors that I have had several classes with was willing to help me out and take part in an interview for this week’s blog post. I interviewed Dr. Vyshali Manivannan, Dr. Mani for short.

Dr. Mani is an assistant professor in the department of Writing and Cultural Studies at Pace University on the Pleasantville campus. Her research focuses are both creative and critical and specializes in medical rhetoric, disability studies, decolonial studies, and online teaching and accessible design. I thought Dr. Mani would be the perfect person to interview for this blog because a lot of my posts are about how I managed my first year of college throughout the pandemic and Dr. Mani is a professional in regards to online modality in a classroom setting.

I started off by asking her what started her interest in writing and how old she was. Dr. Mani informed me that she has been writing since she was young and at the age of 11 wrote her very first fantasy novel (although she claimed it was not super well written since she was only 11). She sent the “fantasy epic” to a publisher and received a response from a publishing agent to “keep writing”. By fifteen, she had written her first proper novel and after a few years managed to get it published. Since then Dr. Mani has had numerous other projects published throughout her career.

I then asked her how she manages to stay motivated with writing and how she managed to keep in contact with peers/coworker/and students during the peak of COVID. Dr. Mani’s response was extremely real and motivating at the same time. She claimed that, “it’s not possible or normal to stay motivated, let alone productive, all of the time. And sometimes a lack of motivation is actually a form of productivity that we just haven’t translated for ourselves yet.” And I genuinely couldn’t agree more.

The start of quarantine took place in the middle of my senior year of high school and any motivation to get work done felt impossible. I had to learn to be patient with myself for not being able to get as much done as I used to or anticipated at the beginning of my senior year.

Dr. Mani also brought up the method of socializing online and how, at least for our generation, it is not such a strange thing to interact with groups online. Dr. Mani is a part of different online communities, specifically online scholarly communities, disability communities, and advocacy groups. Because of this familiar concept, it was a bit easier to remain in contact with people during the peak of quarantine, which, in a way, “kept me motivated while unmotivated” as Dr. Mani stated.

She then mentioned a special issue of a rhetoric journal she co-edited with a group about how COVID has impacted their life and their writing. Having read this special issue, it was an incredibly eye opening and motivating piece. It was written by several people who struggled to continue writing while also trying to take care of their families, and even themselves, during COVID. Dr. Mani mentioned how helping some of her peers edit/write this project had also helped her stay motivated.

When I questioned what Dr. Mani thinks the best way to make connections with students through online learning is, she once again mentioned how communicating online is not an unfamiliar concept. We discussed that especially for my generation (Gen Z), we grew up online so it’s easy to get to know people through an online classroom. Dr. Mani teaches in a unique way and uses Discord for her classes rather than relying on our university’s class instruction portal website. Through different Discord chat channels, we can comfortably discuss our class readings and work as a team to decipher what is going on in our assigned texts. I have found myself interacting with students more effectively in Dr. Mani’s classes than some of my in-person classes. Of course, all students are different and may feel differently, but Dr. Mani has always managed to make the most out of online classes and makes sure that all students feel comfortable within the classroom environment.

A lot of this interview was eye-opening and almost like a breath of fresh air. To see someone as successful as Dr. Mani honestly states that they were essentially not motivated during COVID, and how that is okay, was a relief to me. It is important to value how you feel and if you think you need a break in your work, then it is best to listen to yourself and take that break. Having alone time or talking to people, online or in-person, can help bring you back to your work and feel that passion again. I admire Dr. Mani’s skill of reminding everyone that we are human and we simply cannot do everything all at once. Dr. Mani has published many different projects and repeatedly mentions that it is a long process that requires connections with people, but a process that is worth it.

Summary:

- Dr. Vyshali Manivannan is a professor at Pace University and a successful writer

- She has published a novel, several lyric essays (one of which was nominated for a Pushcart Prize), interactive nonfiction, scholarship, and performance art

- It was difficult to stay motivated during Covid, but by reaching out to people it helped

- A list of questions I asked:

- Your name, career, and anything else you would like to add

- What got you started/interested in writing?

- During the peak of COVID and lockdown, how did you manage to keep your motivation with writing and how did you stay connected to your peers/co-workers?

- What do you think the best way to make a connection with students is through online learning?

- Why is making connections, online or in person, important to you and your career and what advice would you give to your students/aspiring writers?

- If you wish to know more and read more of Dr. Vyshali Manivannan’s work’s her website is here: https://vyshalimanivannan.com/

By Mia Ilie

Mia Ilie is a student at Pace University, graduating in May 2024 with a degree in Writing and Rhetoric and a focus on publishing. She grew up in Rockland, New York and is currently living in Westchester, New York where she attends school and works at a local bookstore. You can always find her with her nose in a book or screaming to Taylor Swift with her friends.

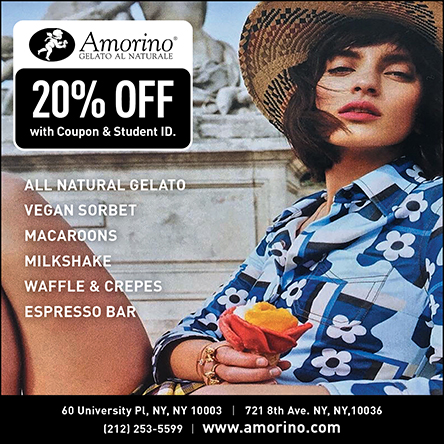

For over 20 years, the Campus Clipper has been offering awesome student discounts in NYC, from the East Side to Greenwich Village. Along with inspiration, the company offers students a special coupon booklet and the Official Student Guide, which encourages them to discover new places in the city and save money on food, clothing, and services.

At the Campus Clipper, not only do we help our interns learn new skills, make money, and create wonderful e-books, we give them a platform to teach others. Check our website for more student savings and watch our YouTube video showing off some of New York City’s finest students during the Welcome Week of 2015.