“Enigma and Light offers up a poetry unlike anything I’ve recently encountered: intelligent, fearless, engrossed in the rigors of its own journey.” – Elizabeth Robinson

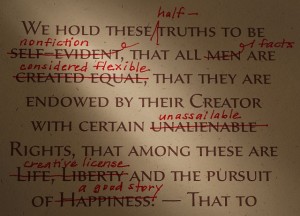

The exercise of ekphrasis – a literary description or critique of a visual work of art, intended to illuminate an essence which reveals itself (perhaps exclusively) in the dialogue between two mediums – is not new. Dating back to ancient times, the term’s original definition extended to a description of anything: person, place, art, or even experience. Rooted in the Greek, ek and phrasis, translating to “out” and “speak;” to literally “speak out” to or identify an inanimate object by name. Unoffically originating in Plato’s discussion of the forms, the rhetorical device can be found throughout literary and philosophical history. Socrates and Phaedrus had ekphrastic discussions. Virgil used it in the Aeneid; Homer in the Iliad; Melville in Moby Dick; Cervantes in Don Quixote. But perhaps the most demonstrative – and notable – use of ekphrasis comes to us in Oscar Wilde’s Sui generis The Picture of Dorian Gray. While it also has robustly traceable roots in poetry, from the work of the Pre-Ralphaelite Brotherhood to William Carlos Williams to W.H Auden, the most contemporary, prominent example is found in the eponymous opening poem of John Ashbery’s Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror (which of course takes its name from Parmigianino’s famous micro-painting). To put it mildly, Ashbery exploded on to the scene following the book’s release, a worthy recipient of what has been dubbed the “Triple Crown” of poetry awards (the Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award, and National Book Critics Circle Award). Ekphrastic poetry has, ever since– more due to Self-portrait‘s notoriety than comparative critical reception – lived in the shadow of Ashbery’s landmark collection.

That is, until now.

David Mutschlecner’s newest book of poetry (author of Sign and Esse) titled Enigma and Light is an exquisitely crafted (a capacity which Ahsahta Press has recently exhibited industry-leading proficiency for) intertextual gateway to a world whose borders are typically only penetrated via hallucinogenic/augmented imaginative assistance. Past its mesmerizing grey-canvas wrapping – once an adequate attention is attained – inside one is greeted with familiar names unfamiliarly juxtaposed to familiar names, as titles. Mutschlecner adamantly takes his departure from the rhetoric’s Platonic origins, and then proceeds to gracefully transcend it.

My own personal experience with ekphrastic discourse goes back to freshman history in high-school, where I had the serendipitous pleasure of encountering one of the most brilliant people I have ever met. Not only was his knowledge encyclopedic, but his diverse and expansive array of areas of expertise would put most encyclopedias to shame (he memorized libraries while we refused to commit even the Bill of Rights). Yet, it was one fairly well known anecdote, haphazardly proclaimed, that has managed to stick with me some 8 years later. Mr. McShane was in the habit of playing music in class, which given his impeccable taste, was a welcome addition to an otherwise traditionally obtuse syllabus. On one such occasion, without warning (as he was also in the habit of doing) he played “Subterranean Homesick Blues” by Bob Dylan, followed by abruptly slamming the pause button (as he was never in the habit of doing) after the line, “you don’t need the weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” If it wasn’t a Dylan song, I don’t know that I, or anyone else in the class, would have even realized the words prior to this anomalous occasion (keep in mind this was around the advent of “artists” such as Lil’Wayne and E40). Of course we would eventually learn that the song and the lyric in particular, was the inspiration behind the Weather Underground, a radical organization started in 1969 which went on to become one of the faces of the New Left.

Dylan somehow (this is another article altogether) captured a zeitgeist buried in young people that they could not bring into aperture themselves. In his art, his message, his essence was the Rosetta Stone they had been waiting for to translate their own ideals (which were more or less parallel to Dylan’s in Blues) into a full-blown movement. To put it simply, it spoke to them, in a language they could finally understand.

David Mutschlecner accomplishes a similar goal, tantalizing his own latent curiosities to uncover ones in the reader he or she didn’t know were there. The poetry grounds its tension in the struggle of a man drowning in ideas and a faith that seem to be at odds. What occurs in Enigma and Light is rare, and does so immediately. A few pages into the opening poem, as David Peak of The Rumpus keenly observes, Mutschlecner gives us six lines that work as a quasi-micro-orientation, a layered ekphrastic invitation itself of what is to come, a revelation of the pulse that sustains each of his scintillating conversations.

“Martin’s marks are Stein’s

word stipplings,

both inter-patterning one anotheras they could not

without the clear delineation—

each word girded by the grid.”

This is the precious commodity with which the poet performs his alchemy. The marks and words which inter-pattern one another, the invisible thread of thought which extends beyond eras, mediums, and death itself between artists and thinkers (and us all) alike. Mutschlecner states in the author’s statement that “seeking the inherit similarity in dissimilars is the work of the Holy Spirit;… this is, to me the highest goal of poetry” (which, unsurprisingly, could just as easily could be the words of Ashbery – less “Holy Spirit”), a pursuit satisfying not just an artistic hunger, but metabolic need to digest the work of those who title his extrapolative discussions. On the surface, Mutschlecner‘s work is a serial poem, but a more perspicacious description would be an amalgam of philosophical discourse, an extended and fragmented essay on art, a treatise on form and message and meaning; a meditation on medium.

Gertrude Stein and Agnes Martin, Martin Heidegger and Ezra Pound, Thomas Aquinas and Emily Dickinson, Robert Duncan and Dante Alighieri, Joan Mitchell and Charles Olson, Georges Rouault and Robert Motherwell: just a selection of the intriguing – to say the least – pairings which compose this unusual and beautiful work. Names like Herman Melville, Nicholas of Cusa, Robert Ryman, Karl Rahner, Saint Faustina and the Gee’s Bend Quilters, alongside so many more, are used by Mutschlecner to sketch a stimulating, abstract, time-bending map of voices he follows until excavating the fault lines where centuries of celebrated art and ideas intersect.

You might be saying to yourself, this idea seems fresh, interesting, intelligent and perhaps even worth the purchase price on its own. But it might also seem a bit pretentious, implying a necessary body of knowledge very few, if any, potential readers will possess upon checkout. Despite the fact that Mutschlecner’s lifetime of intense study and obsession with detail are (albeit quite elegantly) on open display in essentially ever y other line, this is not necessarily the case. This is, because, and not despite, the premise the work takes. By choosing the unknowable, highly subjective domain that exists in these contrived discourses between artists of his choice; using settings mundane as empty rooms and cracks of sunlight sneaking through veiled curtains as his meditative arenas; a vigorous stripping of line and length, producing a perfectly rationed minimalistic prose; Mutschlecner provides ample avenues of accessibility into his own idiosyncratic thought process and associations. The “world view” which reveals itself at the bottom of the glass of this cerebral concoction is an original one. It is a view that comes more and more into focus with every poem, with the diction, pace and measured metronome of each consistently aesthetically pleasing. The grey area that Mutschlecner’s unique combination of knowledge and inquiry inhabits is a place opened to the reader, where he is then able to infuse his own philosophy and curiosities to a discussion that never ends, and if we are to side with our guide, perhaps never was. A place where the patterns of being that are generated only appear to do so; they have been there all along, our experience is simply the recognition, the girding of each word to the grid. Consider an excerpt from “Karl Rahner / The Dusky Seaside Sparrow”:

“There is no improvement

can spark substance. The message dead

in this bottle, and yet the messagestill, is read: Dusky—“Orange”

—Last one

Died 16 June 87tagged to the lid. . . .”

It is in such benign everyday moments, ones we all must tolerate, that our most deeply ingrained (whether through internal or external means) patterns seem to correlate; a phenomena for which Mutschlecner has (perhaps unknowingly) conditioned his eye. It is for the same reasons, we are able to make that eye our own, to see from a place where allusions are the horizon on which “thought rolls and turns and” can be followed to gaze upon our most substantial, and lasting constructs: those composed of agreed-upon meaning.

I highly recommend this new collection poetry not just because of its sublime musicality, but it is educational, provocative, and demands an active and thinking mind beginning to end – most of which without the reader even knowing it. If you’re like me, then it won’t take very many lines to inspire the inner artist in you – regardless of whatever you consider your primary walk of life – so why not use the student advantage provided (below) by your friends at #CampusClipper for some awesome art supplies at Da Vinci (they have a great selection of moleskine notebooks too in case Enigma inspires the poet or writer in you as well!).

Mahad Zara, The University of Arizona and Columbia University, Read my blog and follow me on Twitter

Click here to download the Campus Clipper iTunes App!

Follow Campus Clipper on Twitter or keep current by liking us onFacebook

Interested in more deals for student savings? Sign up for our bi-weekly newsletter to get the latest in student discounts and promotions. For savings on-the-go, download our printable coupon e-book